Rediscovering the Early Irish Church

“A person who has compassion for the needs of his neighbour truly carries the Cross in his heart.”

―Cambrai Homily, written in Old Irish and Latin, ca. 7th C

The oratory at Gougane Barra, where Saint Finbar of Cork († 623 AD) established a monastery.

CC License by mozzercork @ flickr

CC License by MollyCrilly

The Island of Saints and Scholars

Early Irish Christians directed the courage of their forefathers into a new and inward direction: spiritual warfare against their enslavement to evil passions. Their wonderworking enlightener Saint Patrick lived according to the wisdom and practices the Egyptian desert fathers. Following his example, early Irish monastics practiced a mighty ascetic faith.

Later, in a twist of world history, Celtic Christians played an instrumental role in rescuing Western European Christianity. On the brink of dying out, Western Civilisation received an infusion of Christian learning and hope from the faithful Celtic Church.

CC License by Joseph Mischyshyn

PART I: Celtic Lands Become Christian

The Holy Land and Egypt blossomed as a spiritual heart of the early Christian Church until after the Islamic conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries. At the time of Ireland’s conversion to Christianity, the Desert Fathers of Egypt were known for their courageous pursuit of desert monasticism.

Much evidence, both in historical artefacts and culture, reveals a spiritual link between Egypt and Ireland. Saint Patrick and early Celtic monks and nuns kept extreme ascetic disciplines according to Egyptian Desert customs. They fasted from food until their ribs protruded, memorised the Psalms of David, and, like Saint Kevin of Glendalough, prayed in cross-fidel (with their arms outstretched, like a Cross). In explaining the latter custom, Egyptian Saint Paphnutius, in his 4th Century History of the Monks of Upper Egypt, quotes Abba Zacchaeus:

Every person who lifts up his hands as a type of the cross of Christ defeats all his enemies, as did Moses who defeated Amalek by raising up his hands.

Saint Patrick himself prayed all night, memorised the Scriptures, which he quotes often in his letters, and fasting strenuously. He also followed a practice of Egyptian ascetics when he fasted on Croagh Patrick for 40 days during the Lent of 441 AD. For instance, Saint Zosima met Saint Mary of Egypt during a similar fast in which the brothers of his monastery each went out alone to pray in the desert during the 40 days of Lent. At Pascha, they would come together again and celebrate the Resurrection of Life in Our Lord.

Thou my Great Father and I, Thy true son, Thou in me dwelling, and I with Thee One.

– From “Be Thou My Vision“, a Christian hymn written in old Irish by 6th C. Bard Saint Dallan Forgaill.

Devoted Scribes and Poets

In the context of the Early Church, Ireland earned its ancient title of the Insula Sanctorum et Doctorum—the Island of Saints and Scholars. Early Celtic societies relied on poetry and song to shape the meta-narrative of the clans through the position of a bard. Appointed by the king, bards preserved the collective memory of the clan while intelligently exploring themes of history, culture, and the deeper realities of life. When Christianity brought literacy to Ireland, many bards took up the pen and became gifted scribes, among the most remarkable in Europe at the time. Often tonsured as monks, these scribes carefully preserved their own heritage as well as the classical literature of the dying Roman world.

Irish Bard Saint Dallan Forgaill wrote the hymn Be Thou My Vision in the 6th C. as a testament to his spiritual relationship with God. An enduring favourite, it remains even today in both Protestant and Catholic hymnals. Though the position of monastic scribes and bards eventually declined, their legacy continues in the extensive body of early Irish Christian literature, as well as in the rescuing of many ancient texts which otherwise might have been lost.

CC License by Yeats

Irish Clochán

Irish ascetics, like their Egyptian desert fathers, sought out the solitude and exposure of wilderness. They built their monasteries on remote islands, in caves, and deep in forests. With drenching rain and gales, however, Ireland’s climate could not be more different than the Saharan Desert of Western Egypt.

Rather than the Egyptian monastic cells of mud brick huts and palm tree roofs, thus, Irish monastics along the western coast often laid drystone into beehive-shaped cells, called Clochán. Clochán in old Irish can mean both “stepping stones” and “little stone cell.” The careful corbelling techniques employed by the monks ensured that the cells remain even today dry and sheltered, despite frequent hurricane-strength winds.

Our town of Clifden is called, in Irish, An Clochán. Some locals believe that it’s named after an ancient Clochán which once stood in Clifden’s old Catholic cemetery.

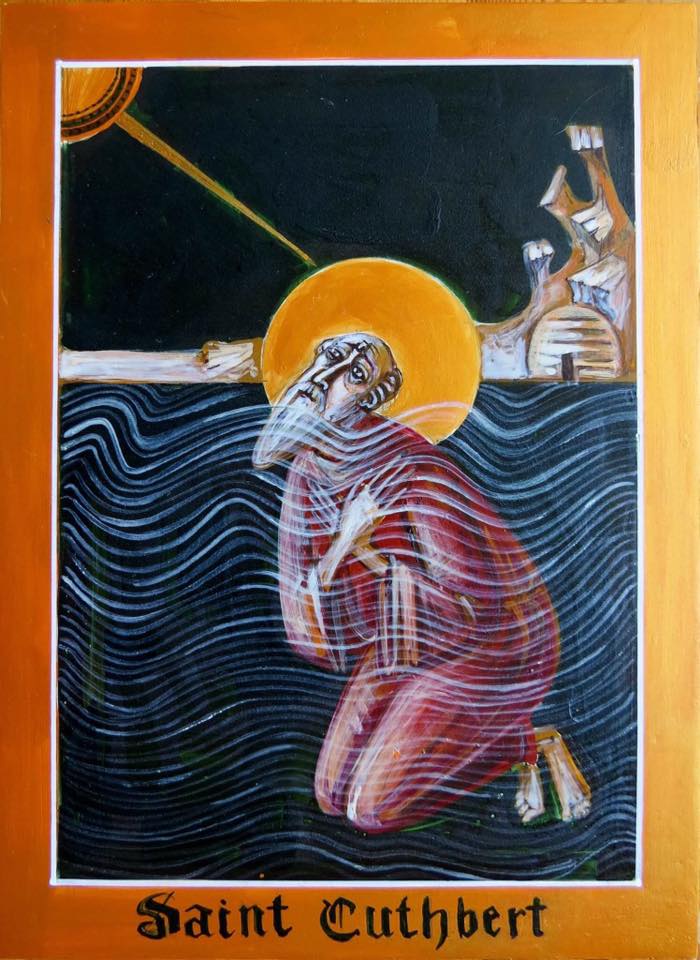

Praying in Water

Availing themselves of their chilly, wet climate, Celtic Christians also prayed while immersed up to their neck in outdoor water. Saint Adomnán prayed every night in the River Boyne in Leinster. Many Celtic monastics prayed in Holy Wells, also used for baptisms, of which over 3,000 dot the Irish countryside. Folklore recalls that Saint Féichín “knelt and prayed while immersed in the cold water” of Doaghfeighin (St Féichín’s Bath).

Early records refer to the common Celtic practice of praying in outdoor water. Among the many hagiographies featuring the practice, a few stand out. Venerable Bede records an account of Saint Cuthbert of Lindesfarne, whose monks worried about his nightly sojourns. Secretly following him, a brother watched as Saint Cuthbert reciting psalms all night in the English Channel with otters ministering to him thereafter.

Even Saint Patrick prayed in water according to the earliest hagiography of Saint Patrick. The 7th C account by Muirchú describes Patrick praying in the middle of a river bed with his successor, the young Saint Benignus, who was unable to bear the cold.

CC License by Andreas F. Borchert

Wonderworking Gifts of Asceticism

Though colourful exaggeration distorts some legends, the spiritual heights which Celtic saints attained are apparent in their hagiographies. Like many Saints of the Orthodox Church, including those of recent memory, early Celtic saints worked wonders, saw with clairvoyance, healed, befriended wild animals, and even raised people from the dead.

The healings and miracles of Orthodox ascetics are neither fearsome nor magical. Instead, they reflect the ultimate truth of Christ and His triumphant Resurrection over entropy and death. When Saint Patrick fasted 40 days and nights on Croagh Patrick, like the Egyptian Desert Fathers who followed such practice, he enthusiastically pursued such faith. Their example demonstrates a proper understanding of God’s reality:

Isaiah 40:31 – “But those who hope in the Lord will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint.”

As our ascetic Holy Fathers and Mothers bear witness, a lifetime of strenuous pursuit only begins to comprehend the actuality of God and His infinite love for mankind.

PART II: Rescuing Western Christendom

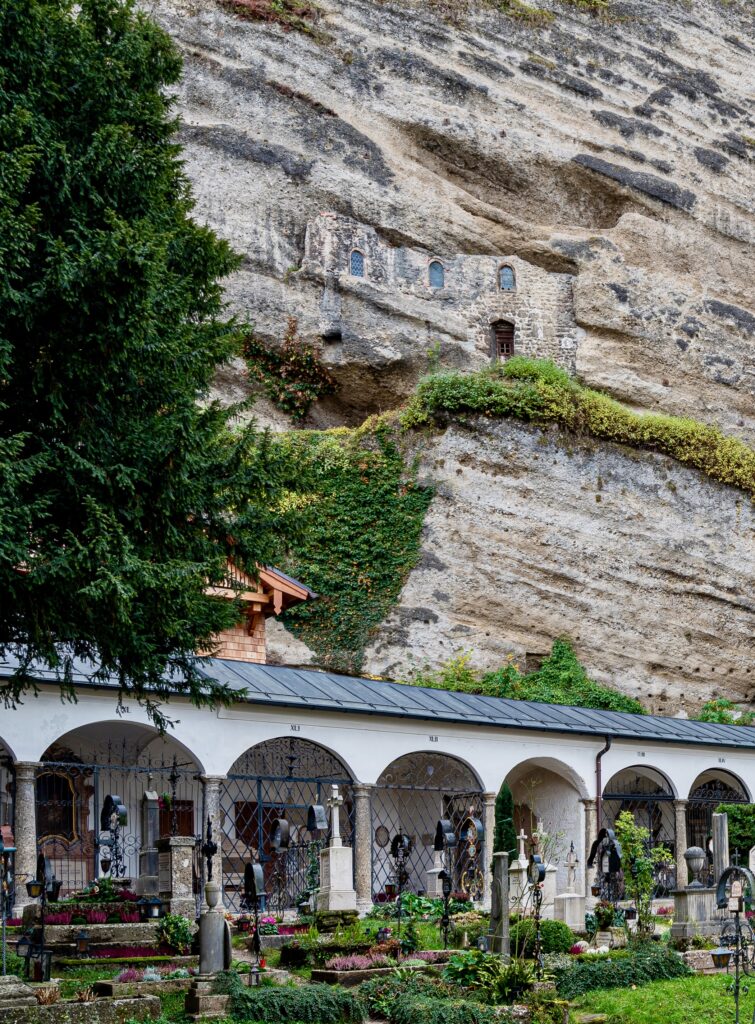

When Celtic missionaries came to Western Europe during the 7th and 8th centuries, they found Christianity to be scattered and nearly forgotten. Christian remnants often survived in isolated pockets. For instance, by the time Saint Rupert discovered a Christian remnant settled along the Wallersee, it had survived for nearly 200 years, since the time of Attila the Hun in the 5th century, with little clerical oversight or liturgical practice.

Among the surviving churches, Arian heresy and other heresies abounded. Many of the Germanic tribes who had settled down remained pagan. Others followed corrupted Christian ideas and practices. In Burgundian France, Irish-born Saint Columbanus found the situation to be dire:

The Christian Faith had almost departed from that country. The Creed alone remained. But the saving grace of penance and the longing to root out the lusts of the flesh were to be found only in a few. Everywhere that he went the noble man [Columbanus] preached the Gospel. And it pleased the people because his teaching was adorned by eloquence and enforced by examples of virtue.

―The Life of Saint Columban, by the Monk Jonas, (7th Century), translated by Munro, Dana C., Internet History Sourcebooks.

Moved to compassion by the state of the Christians they encountered, Celtic missionaries such as Saint Columbanus laboured throughout Western Europe to encourage, instruct, and reinvigorate the Church.

Photo by Bonifatius Stirnberg on WikiCommons.

The Call of White Martyrdom

These Irish-trained missionaries followed an ascetic practice known as White Martyrdom. According to the 7th century Irish Cambrai Homily, red martyrdom meant dying for the Faith and green martyrdom implied severe asceticism, such as fasting and nightly vigil. White martyrdom, meanwhile, meant “when they part for the sake of God from everything that they love.” The homily thus expounds on the virtue:

A person who has compassion for the needs of his neighbour truly carries the Cross in his heart.

―The Cambrai Homily, written in a mixture of Old Irish and Latin, ca. 7th Century.

Irish missionaries, upon seeing the disheartened and superstitious fragmentation of these European communities, often displayed inspired boldness. Irish missionary Saint Gallus (namesake of the city in Switzerland) stole pagan idols, rowed out to the middle of Lake Constance, and drowned them. Though ready to kill him at the time, the local Germanic tribes eventually became persuaded by his Christian example. From his hermitage deep in the bear- and wolf-inhabited alpine forest, Saint Gallus instructed disciples as St. Magnus in the quiet sweetness of the Christian Faith.

CC License by ErwinMeier

Celtic Faith Etched into the Corners of Western Europe

Many of these Celtic Saints have been forgotten in Ireland yet remain beloved in the corners of Europe where they settled. Italians remember how the Irish prince Saint Fridianus, through prayer, saved the city of Lucca from a raging Serchio river. Germans still recall how Irishman Saint Fridolin of Säckingen briefly woke a dead man to settle a legal dispute. The miracle so astonished the community that many converted to Faith, including the disputing brother.

Even when the names of these missionaries have been lost, the legacy of their faith endures. Locals of Murnau, Germany, for instance, still cherish an iron bell, similar to this one, brought to the region by Celtic missionaries. Thought to be made in Iona, the bell hangs in a church referred to by locals as the Ähndl, or ancestor-church, from which all other churches in the region are descended.

Many delightful hagiographies could be added. Almost every corner of Western Europe includes foundations laid by Celtic missionaries. Thus, after centuries of devastating violence and neglect, the White Martyrs of Ireland and the British Isles rekindled Christianity in Western Europe. One could even say that the Early Celtic Saints saved Western Christendom!

Oh my dearest friends, is it unknown to you that no pride of worldly life can prevent me from setting out for that exile which Heaven has indicated?

―Saint Fridolin of Säckingen, Irish missionary to the Rhineland.

Quote from “Rude and Religious Irish”: The Cult of Wandering Saints in the Middle Ages, by Dermot Quinn

See More

The Egyptian Desert in the Irish Bogs, by Fr. Gregory Telepneff, examines the extensive evidence of influence from Egyptian desert asceticism on the early Irish Church.

The Celtic Monk - Rules & Writings of Early Irish Monks, translated and annotated by Uinseann Ó Maidín OCR, presents several writings of the early Irish monastics with insightful commentary and footnotes.

How the Irish Saved Civilisation, by Thomas Cahill, offers a warm and telling glimpse into how vital a role the early Irish Church played in saving the classical libraries of Europe.

Everywhere Present: Christianity in a One-Storey Universe, by Fr. Stephen Freeman, about breaking down doubts and detached concepts of reality in order to commune with Christ in our everyday life.