The History of Shanakeever Valley

The Gloomy Slopes

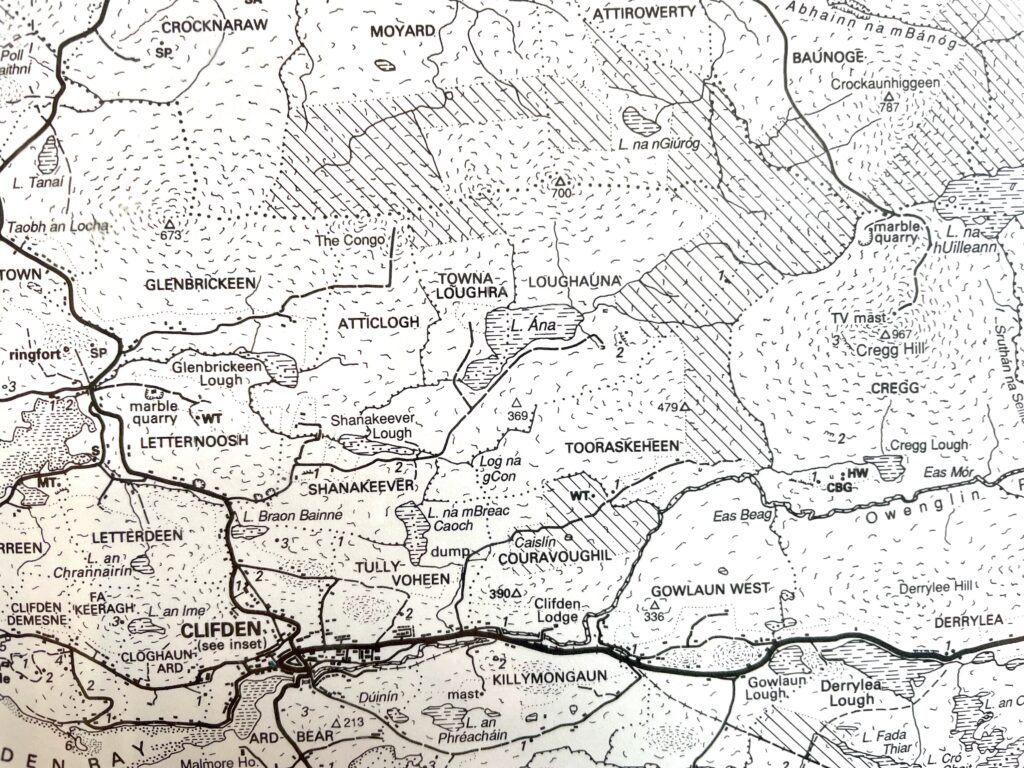

The Shanakeever Valley, Seanad Chiamhair in Irish, means gloomy slopes. The water descends through three lakes as its waters flow out to the Streamstown estuary about a mile away. The lakes, in descending order, are Loughauna, Shanakeever, and Glenbrickeen (from Gleann Bricín, which means Valley of the Brown Trout.) Though beautiful, it perhaps takes its name from the sad history which much of the island witnessed in the recent centuries.

Prehistoric Traces

Evidence for human settlements in Shanakeever Valley extend back into the earliest records of human migrations. In particular, a concentration of prehistoric markings exist at the north end of Loughauna. These include a grove of ancient Hawthorn trees near an ancient cave dwelling and a 6,200 year old Dolman burial tomb.

An Enduring Way of Life

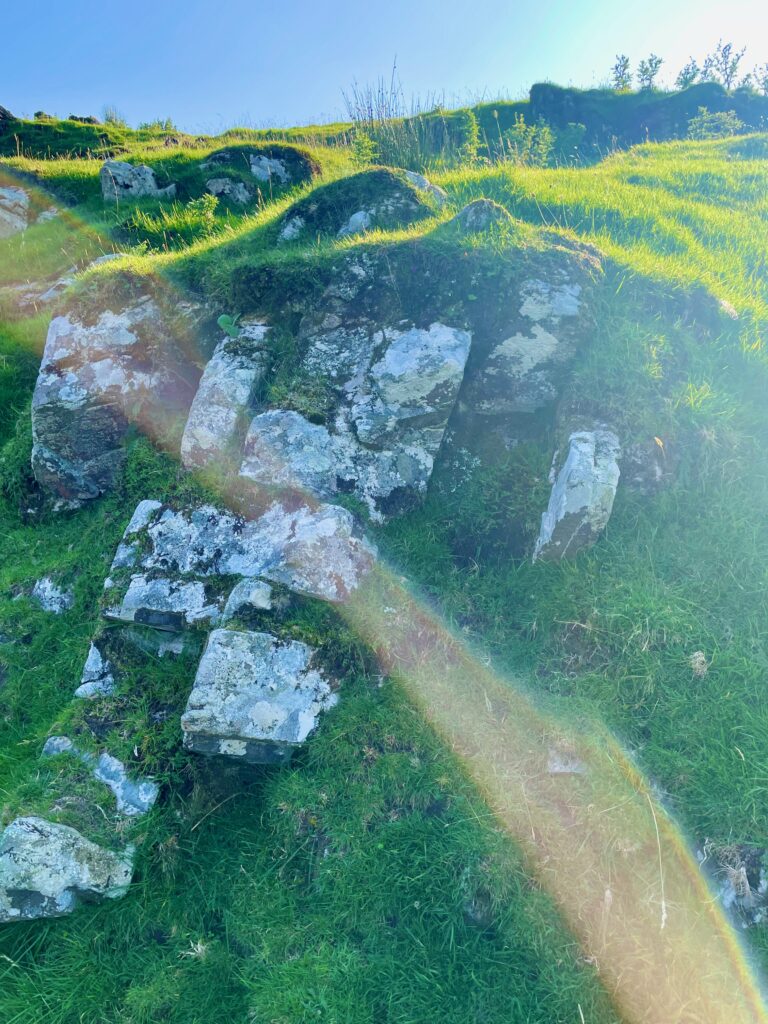

The lifestyle of the people here on the windy Connemara bogs changed little over the centuries. A semi-nomadic pastural economy known as booleying continued well into recent history. Even early 20th C. walls, homes, and other structures were made as they ever were, with the skillful laying of stone. One wall near Loughauna, whether constructed several hundred years ago or possibly eighty, even includes a place to sit down:

Another ancient practice that continued up until fairly recently is the establishment of small wind shelters. Dug out next to a boulder or ditch, the farmer would have huddled here with his livestock during the fierce winter storms sweeping through the valley:

Most of the historical settlements are found north of Loughauna – Loch Ána. Some historians guess that the lake’s name refers to the girl’s name (Anne’s Lake) but former owner Tom Joyce believes the name in old Irish refers to the curved shape of the lake – Lake of the Bend. He also claims to have seen in Loughauna an Each-uisce – a mythical water horse (the Irish version of the Loch Ness monster). In fact, the Clifden library offers a whole scrapbook full of eye-witness accounts of the water horse of Loughauna.

Connemara Marble

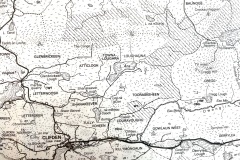

The rock bed of the Shanakeever valley is largely metamorphic and includes a vein of the highly prized Connemara marble. A marble quarry operates at the head valley, north of the Cregg mountain (the crag so often featured in our sunrises).

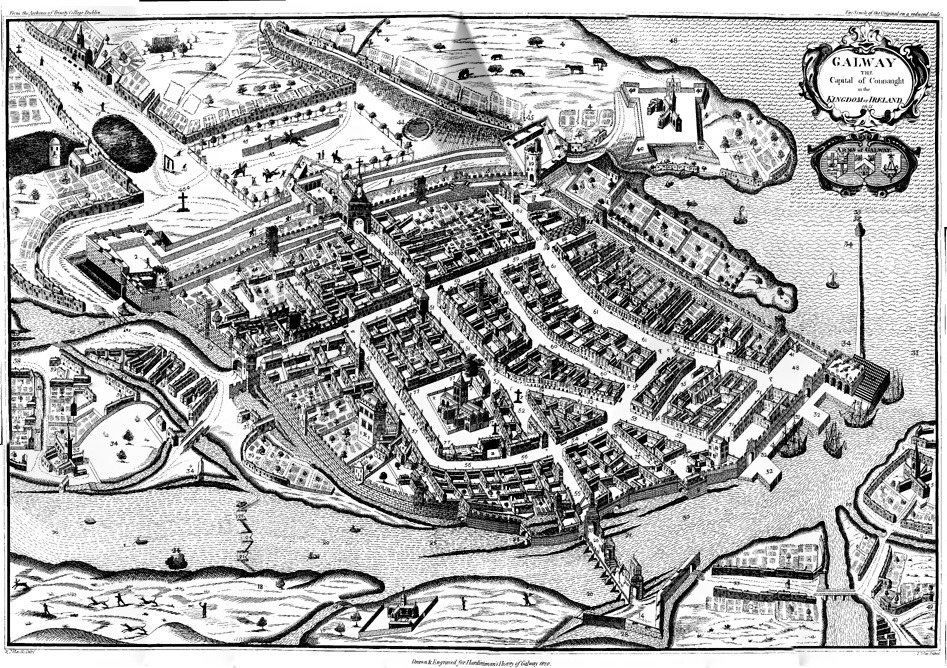

“Go to hell or to Connacht!”

Image: British Library HMNTS 9508.ccc.14.

Oliver Cromwell allegedly pronounced this sentence against the native Irish. As the Cromwellian conquest (1649–1653) confiscated Irish lands, many refugees fled or were forced to the remote western region of Connacht, of which Connemara is a coastal branch. For over a century, Penal Laws dispossessed the traditional Irish of their land ownership, language, means of living, and subjected them to systematic impoverishment and outlaw status. Irish “rebel” warriors became hunted for head bounties along with Catholic priests and the last of the native wolves:

A Secret Mass Rock

In the forests at the north end of Shanakeever, there is a clearing where locals used to gather during these hard times for illegal celebrations of Catholic Mass. This Mass Rock continues to see local visitors and still blooms every spring with daffodils, as experienced by the neighbour whose photo this is:

The Wild West Coast

The boggy and fractal Connemara coastland, being difficult to farm or access, meant that the region was among the poorest in the island. Some oral reflections about the region by an old smuggler named George O’Malley reminisce about these earlier times. He was recorded around the turn of the century and published in 1911 in James Barry’s Tales of the West:

There was no road of any kind in this wild, vast region, not even a beaten path. There was no chapel in some of the parishes, no priest’s residence, no school of any kind, no post office, no dispensary, no court of justice, no police barrack for there was no police until 1893…

George recalls earlier stories passed down of people coming to Connemara from other regions of Ireland, displaced by the Cromwellian conquest:

…they came in hundreds, and were received by the natives with open arms. The next thing they did was to take native wives, for the Connemara maidens of those days were easily wooed and won, and in a generation or so afterwards the result of this intercourse was a race of mortals the most heterogeneous to be met with in Western Europe. This was not a type to be seen amongst the Caucasian race, scarcely, but its prototype could be seen in that strange, wild region, but the great famine and emigration cleared them out.“

Vanishing in the Great Famine

The Great Famine of the late 1840’s caused catastrophic death and suffering in Ireland. Connacht ranked as the region hardest hit, with some historians estimating that 25 % of its population died in the first five years. The famine’s effects fell disproportionately on native Irish speakers such as those living in Connemara. According to a book by Kathleen Villier Tuthill, around 23 people lived in the settlement north of the Shanakeever valley in 1840, only 3 in 1850 and none in 1853:

Our home belongs to a settlement in Atticlough (Áit tí Cloch – Place of the Stone House). The name may refer to our neighbour Paddy’s house, but the abrupt disappearance of the valley’s folk during the Great Famine means that no one really remembers. Another ruined structure also exists which may also have been a house:

Lonely Slopes

As wind blows through the Shanakeever valley, it moans and howls at Piper’s Hollow, a corner at the southeast bend. In the wake of the famine, severe economic turmoil caused a mass exodus of Irish refugees to communities around the world. These post-famine haemorrhages lasted for several generations. Our American family, for instance, traces our Irish heritage to the 1860’s, through Ellis Island.

According to Wikipedia, 40% of Irish-born people lived abroad by the year 1890. By the 21st century, an estimated 80 million people claiming Irish ancestry lived outside of Ireland, making it one of the largest diaspora in the world.

Trying to Recover

Meanwhile, hungry lads used greyhounds to hunt hare in the deserted Shanakeever valley. To this day, a corner of the valley goes by the name Luagh na gunn or Log na gCon, or “meeting point of the hounds”. Back then, a clear hare-coursing run would have stretched without roads or fences up to the famine ruins. Locals remember another coursing slope at Nun’s Hill near Tawnaloughra (Tamhnaigh Luachra, which means “arable patch of rushes).

Hare-coursing is the subject of a well-known song about the valley, Bogs of Shanaheever. The ballad follows a lad whose favourite dog dies while chasing a hare over a cliff. He sadly packs up and leaves for America. Bruce Folley sings a version of the song whose lyrics correctly spell the local names. Believed to be based on a real event, local historians have pin-pointed the place where Victor the dog would have died. We can see it from our front door, circled here in red:

Turf-Cutting into the Bog

On the northern slope of the Shanakeever lake lies extensive blanket bog. One can still see the rows in the land from pre-famine potato cultivation, and the square ridges from cutting turf (burnable peat, for making fires) with a hand-held sleán:

The valley opened up for widespread turf-cutting in the 1950s. A neighbour grew up on Omey Island and remembers coming to the Shanakeever valley as a boy to cut turf with his family. Often barefoot, they would walk the 15 or so kilometres, about 3-4 hours each way. There, rain or shine, the whole family would work all day, cutting turf with a hand-held sleán, turning, stacking, and finally carrying them home. “It was pure slavery,” he laughs.

Memory Eternal

As part of the research of the valley’s history, our neighbours offered several songs as favourites to reflect the themes and heartaches of the area. Processing of difficult emotional realities through song is a peculiar and enduring aspect of Ireland’s bardic culture. One struck a chord with me. It speaks, perhaps, to the value of preserving memory as a spiritual act. As Orthodox Christians, we pray for the dead through the act of remembering: “Memory Eternal.” Remembrance, without getting caught up in the emotional turbulence of grief, becomes to attempt to live according to God’s dispassionate peace:

Viewing death, corruption, and tragedy as final acts underestimate the subversive power of Christ, whose own crucifixion destroyed death itself. Christ promises ultimate deliverance, drying up every tear and even re-enlivening the bones of the valley: “In the world ye shall have tribulation, but be of good cheer: I have overcome the world. (John 16:33)” As we take up residence in the Shanakeever Valley, we remember the ones who came before: may their memory be eternal!

A Visual Tour

The photos can also be viewed here, in an expandable format: