Traces of Egypt in the Ancient Celtic Faith

“It is patience that reveals

every grace to you, and it is through patience

that the saints received all that was promised to them.”

―Saint Pachomius the Great of Egypt

Saint Comcille’s Arch in Disert, Co. Donegal. Also spelled díseart in Irish, such a place-name often refers to an old monastic hermitage in the area. These Irish “deserts”, though lush and green, trace back to the practice of desert monasticism as introduced from Egypt. According to the Irish national database, there are at least 76 places scattered throughout Ireland which are named “By the Hermitage”, or An Díseart. Photo: Archeological Institute of America.

Saint Patrick’s Spiritual Heritage

The Spiritual Heritage of Saint Patrick

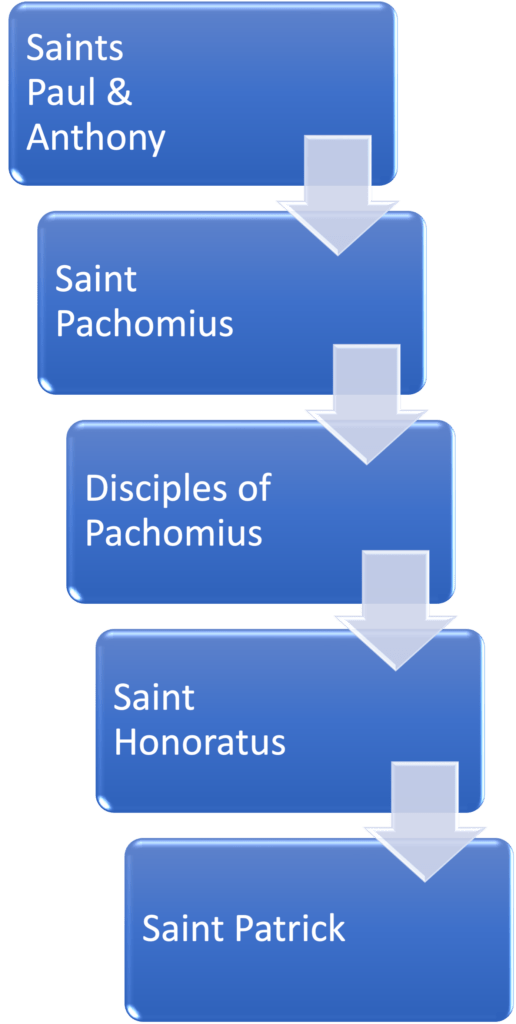

The Orthodox monastic tradition of today originated in Egypt in the 4th Century. Saint Pachomius the Great († 348 AD) received the first rules of asceticism, according to tradition, from an angel. His disciple, Saint Basil the Great († 379 AD), used the Rule of Saint Pachomius as the basis of Orthodox monastic asceticism. This spiritual lineage continues today, passing unbroken from spiritual fathers and mothers to their spiritual children across the centuries.

During his visit to Egypt during the late 4th century, Saint Honoratus of Lérins († 429 AD) would have acquired his ascetic spiritual practices from Saint Pachomius’s spiritual children. Very possibly, he learned from men who personally knew and learned from Saint Pachomius.

In 404 AD, Saint Jerome († 429 AD) translated the rule of Saint Pachomius into Latin, and in 410 AD, Saint Honoratus established his Abbey in Lérins, France. He based the monastery’s spiritual structure upon the rule of Saint Pachomius. Scholars believe that Saint Patrick studied and took tonsure at Lérins Abbey at some point between 410 AD and 433 AD. It is likely that Saint Honoratus mentored Saint Patrick personally.

Saint Pachomius, in turn, learned his ascetic practices from his spiritual father, Saint Anthony the Great († 356 AD), who himself met and learned from Saint Paul of Thebes († 341 AD). In fact, Saints Paul, Anthony, and Pachomius had all died a within two generations of Saint Patrick’s birth (ca. 385 AD).

Thus, the inheritance from spiritual father to spiritual son passed from some of the greatest Egyptian desert fathers to Saint Patrick—and then to Ireland!

Let us take refuge in the Lord and ascend a little to the place where thoughts dry up and stirrings vanish, where memories fade away and the passions die, where human nature becomes serene and is transformed as it stands in the other world.

― St. Isaac the Syrian in his Ascetical Homilies. Desert fathers were exposed to extreme dangers, such as heat, cold, thirst, famine, and the teeth of real lions. But the most dangerous threat of all—against which they courageously warred—lurked in the treachery of their own thoughts, secret fears, and delusions.

Evidence of Shared Faith

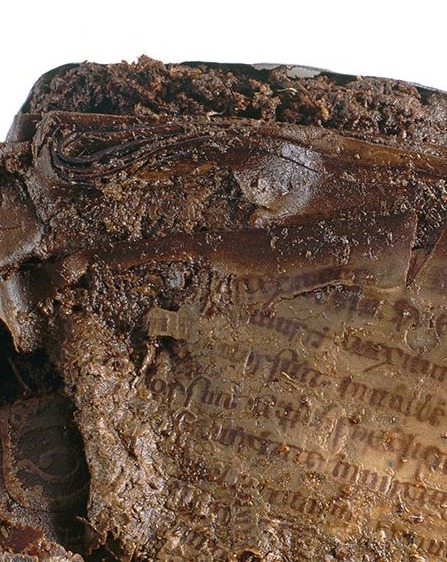

Notable artefacts of an Irish-Egyptian connection include the papyrus lining of an ancient Irish psalter. Oengus of Tallaght, in his ancient accounts of Irish history, remembers seven Egyptian monks buried in County Antrim. In fact, despite Ireland’s rainforest climate, several ancient Irish texts refer to desert monasticism by name. These include the Book of Armagh, the Book of Leinster, and the Annals of the Four Masters. The Stowe Missal, for instance, prays,

May God protect us from the dangers of the desert, and may he grant us the grace of following the example of Anthony of Egypt.”

Also, Ireland’s High Stone Crosses consistently feature Egyptian desert fathers Saints Anthony and Paul. Irish Illuminated manuscripts, moreover, such as the Book of Kells distinguish bishops with Egyptian rather than Roman regalia, such as Tau crosses, stylised crowns, and processional fans. These, and other links, demonstrate the influence of Egyptian desert monasticism on ancient Celtic Christianity.

CC License by Christophe Jacquand

Kindness over the Sword

Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Early Church is simple Christian kindness. Forcefully taken from his home and family, the young Saint Pachomius, along with several other youths, found himself conscripted by the Roman army and sent to Thebes. Despite the scorching heat of the Egyptian sun, the Roman soldiers locked them behind bars to suffer without provisions. Strangers, however, brought food and water without charge, much to the surprise of Saint Pachomius. He inquired and learned that they were Christians, who “treat us with love for the sake of the God of heaven.” Touched by their kindness, he made a vow to serve the Christian God with his life—which he did! Saint Pachomius eventually became one of the greatest Orthodox saints, and a founding father of communal monasticism.

―From the Bohairic Life of Saint Pachomius.

See More

The Egyptian Desert in the Irish Bogs, by Fr. Gregory Telepneff, examines the extensive evidence of influence from Egyptian desert asceticism on the early Irish Church.

Histories of the Monks of Upper Egypt and The Life of Onnophirus, by Paphnutius, a 4th C Egyptian ascetic who sought out and learned from the "perfect ones" living amid the most barren stretches of the Egyptian Sahara.

Ascetical Homilies of St Isaac the Syrian, in teachings translated from the Greek and Syriac by the Holy Transfiguration Monastery, Saint Isaac, a 7th C desert monastic in Arabia shortly before Islamic ascendancy, offers gems of insight and understanding.